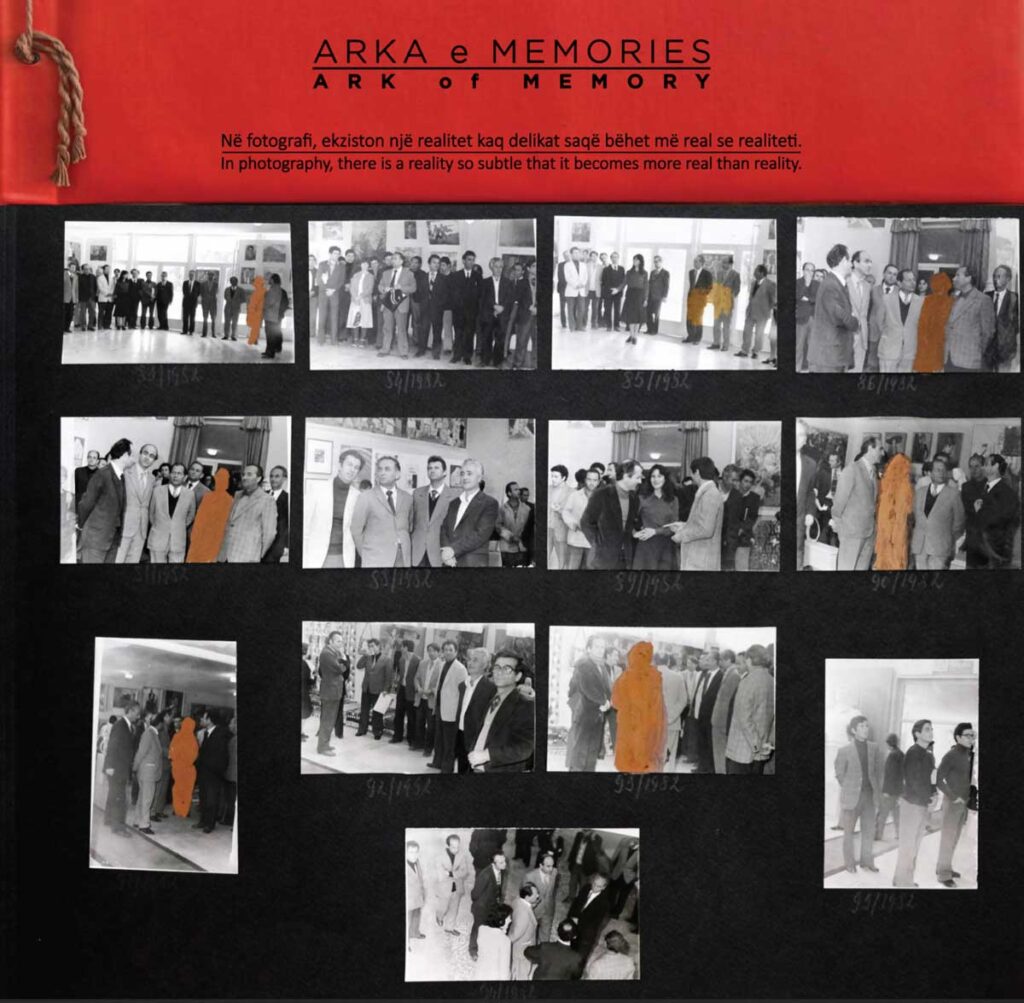

"Moments" - Elton Koritari - Art Curator / 25.08.23 / 15:00 - 16:00 /

Barabar Centre - Grand 4th Floor

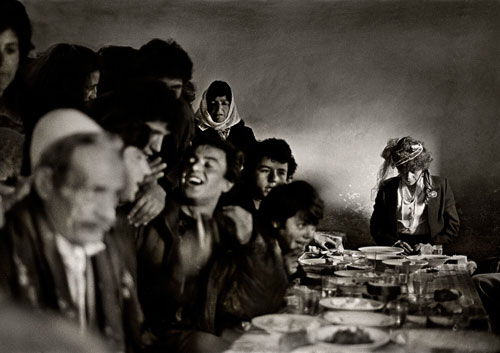

“All these years, I have made contact with photography from any angle possible. As a result, I have come to embrace the conviction that photography just appears to be born as a creation of the moment – produced and consumed instantly. Photography – even if only due to its instantaneous nature – picks one moment out of the stream of time and sends it to eternity. It can grasp the sense of time better than any other form of visual art. Otherwise, Robert Frank insisted that the photograph should contain something important within it, which he defined as the humanity of the moment. With this kind of approach, in this masterclass we will try to learn how to face all the other challenges; in photography, in art, in life.”

ELTON KORITARI

EJAlbum founder and administrator, project manager and curator of art and cultural events, specially focused on photography. Elton Koritari has been working in the Creative Industry for years, managing art projects, curating exhibitions, directing communication campaigns and also representing in Albania some of the most important brands in that sector. From Venice Biennale to Photography Festivals or everything else, he’s work is mainly focused on research about communities, social activism and visual education.

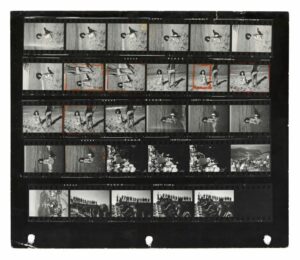

"Tendencies in Contemporary Photojournalism" - Ziyah Gafic / 25.08.23 / 17:00 - 17:45 /

Barabar Centre - Grand 4th Floor

The lecture: “Tendencies in Contemporary Photojournalism” takes a sharp look at the status of art and documentary photojournalism. At the seminar you can experience presentations and debates, which from different angles take important photographic trends under consideration. The lecture focuses on how photojournalism exchange with other fields and the pushes of documentary photography in new directions and about the phenomenological and perception-psychological interest that characterizes contemporary photojournalism.

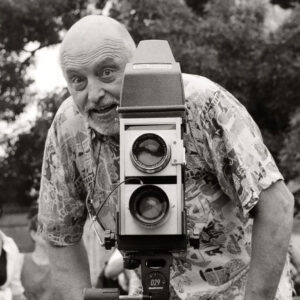

ZIYAH GAFIC

Ziyah Gafic (1980) is an award-winning photojournalist and videographer based in Sarajevo focusing on societies locked in a perpetual cycle of violence and Muslim communities around the world. He covered major stories in over 50 countries. Ziyah’s work received many prestigious awards such as multiple awards at World Press Photo, Grand Prix Discovery of the Year at Les Rencontres d’Arles, Hasselblad Masters Award, City of Perpignan Award for Young Reporters at Visa pour l’Image, Photo District News, Getty Images grant for editorial photography, TED fellowship, Prince Claus grant, and Magnum Emergency fund grant. His work is regularly published in leading international publications. Ziyah authored several monographs including “Troubled Islam – short stories from troubled societies”, “Quest for Identity,” and the most recent, “Heartland.”

"Sarajevo The Longest Siege" - Amra Abadžić (Book Promotion) / 25.08.23 / 18:00 - 18:45 / Kosova National Library

This book is just one little reminder of life during the siege. A reminder of events, people and bravery that we must not forget, and the enormous sacrifice that the people of Sarajevo and their city made to defend themselves from fascism, to preserve the idea of a multi-ethnic, cosmopolitan city, open to all people of good will. It is a testament to the fact that Sarajevo and its citizens were true heroes and that we must be always remain proud of ourselves, our city and how we prevailed with dignity in the face of brutality. This book cannot answer the question of why the world watched the horrors of the siege unfold for 3 years, 10 months, 3 weeks and 3 days in a city located in the heart of Europe with almost half a million inhabitants, in front of the world’s public, in front of world cameras, and did nothing to stop the slaughter. It can, however, provide an insight into what life was like for ordinary citizens of Sarajevo throughout the longest siege in modern European history.

Amra Abadžić

Bosnian-British journalist, historian and translator Amra Abadžić was born and raised in Sarajevo. At the start of the Siege she joined the Reuters News Agency, and from 1992-1995 she covered every aspect of the conflict including the front lines, press conferences, hospitals, funerals and the morgue, and daily life. After the war she worked as the project manager for Bosnia Herzegovina Heritage Rescue, protecting and restoring the cultural heritage of the country. She has also worked for many NGOS, and on numerous journalistic, documentary and film projects. She holds a BA in Modern History from the Open University in the United Kingdom.

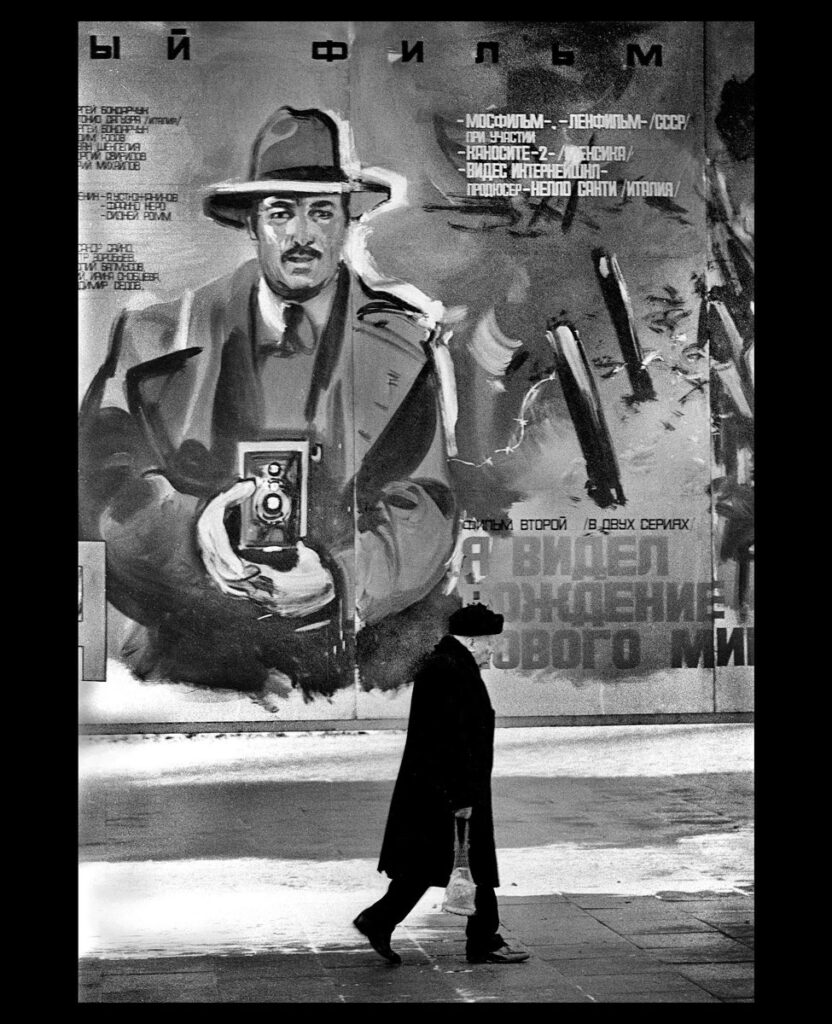

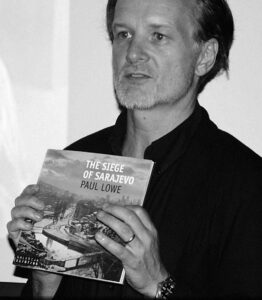

"Testimonies of Light: Photography, Witnessing and History" - Dr. Paul Lowe / 26.08.23 / 11:00 - 12:00 /

Barabar Centre - Grand 4th Floor

In its relatively short history, photography has arguably become the predominant medium through which we represent the world around us. It is hard to imagine a world without the photographic image, so ubiquitous has it become as a form of communication, documentation and personal and artistic expression. Today, more photographs are taken every two minutes than in the whole of the nineteenth century. We now photograph everything, every moment of our lives and the world around us. Photography has arguably become the means through which we most strongly remember the past – and represent the present – forming the foundation of not only our collective social memory, but also our personal memories. Photographs capture a moment in time and in space, condensing and concentrating experiences into artifacts. They preserve within the frame the ghostly traces of the past as well as the knowledge that that past is no longer there, and therefore serve to preserve our sense of history and memory. As such, they form an important part of remembering, fluctuating between past and present, connecting moments in time. This is not necessarily a “stilling” of time, but rather a concentration of experience into an image that suggests time interrupted, retaining the sense of a time before the image and a time after it. As soon as the shutter closes, that moment of representation is forever in the past, yet still preserved in the present and into the future. The paradox is that although the still image is a single, discrete temporal event, it has the ability to transcend time; by playing on the imagination of the viewer, it can project backward and forward through time. The image retains within the frame a self-contained story, a sense of occurrences before the photograph and possibilities afterward. This presentation will therefore explore how the photographic image has engaged with the historical moment, from its inception in the mid nineteenth century to the present day.

Paul Lowe has worked as photojournalist since 1988, represented by VII Photo covering news and current affair stories in over 80 countries, including the fall of the Berlin Wall, the break-up of the Soviet Union, the destruction of Yugoslavia and the war in Bosnia. He is Professor of Conflict, Peace and the Image at London College of Communication, University of the Arts, LondonI

"Kosova War to Drini River Project" - Ferdi Limani / 26.08.23 / 12:00 - 13:00 / Barabar Centre - Grand 4th Floor

In an up close and intimate open discussion Ferdi Limani will share his work from early Kosovo war aftermath to most recent environmental project on Drini river while discussing with the audience the steps he took in a complex Kosovar media market.

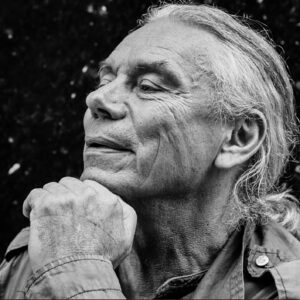

FERDI LIMANI

Born in 1982 in Prizren, Kosovo. In the late 90’s when his birthplace was in the middle of atrocities, Ferdi realized the importance of documenting history. After journalism studies he began working for daily newspapers in Kosovo and collaborated with international news agencies. His work culminated when he was commissioned by the Government of Kosovo to document the independence declaration. He produced work for various French and international media in Europe, Middle East and the Balkans. Besides his freelance work he is a Getty Images contributor.

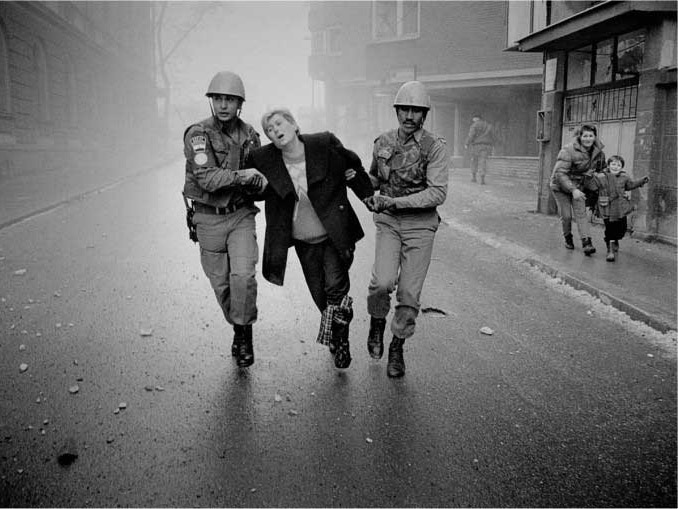

"Siege of Sarajevo" - Dr. Paul Lowe / 26.08.23 / 13:00 - 14:00 /

Barabar Centre - Grand 4th Flool

“Siege of Sarajevo”

Paul Lowe witnessed the terrible everyday life of the citizens of Sarajevo, but also their spirit of resistance. The siege of Sarajevo – the longest siege of a capital city in modern history – started in April 1992 and ended in February 1996. During the four-year siege, over 10 000 people were killed and 60 000 injured, from a population of 350 000 – which meant a one-in-five chance of being hit by sniper fire or a mortar shell. His photographs captured during the siege of Sarajevo document everyday life of people of Sarajevo. They reveal two sides of the story about besieged Sarajevo – on one side, this is a story of suffering and four years of uncertainty, but on the other side, it is also a story of incredible courage, creativity and perseverance.

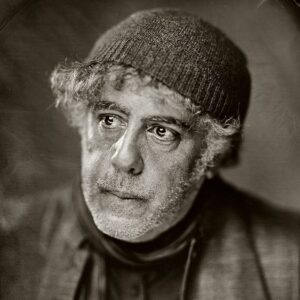

PAUL LOWE

Paul Lowe has worked as photojournalist since 1988, represented by VII Photo covering news and current affair stories in over 80 countries, including the fall of the Berlin Wall, the break-up of the Soviet Union, the destruction of Yugoslavia and the war in Bosnia. He is Professor of Conflict, Peace and the Image at London College of Communication, University of the Arts, London.

"AI: LET THE GAME BEGIN" - Panel Discussion / 27.08.23 / 15:30 - 17:00 /

Kino ARMATA

“AI: Let The Game Begin” – Panel Discussion

In the evolving landscape of photography, the symbiotic relationship between AI and human creativity has emerged as a compelling theme. As technology advances, AI’s integration into the realm of photography has provided novel tools for artists and enthusiasts alike. From automated image enhancement to algorithm-driven composition suggestions, AI has expanded the possibilities of visual storytelling. However, this integration also sparks discussions about the ethical dimensions of AI-generated content and the potential loss of human touch in the creative process. The dialogue between AI and human photography at FOTOIST – International Photography Festival delves into the balance between innovation and authenticity, exploring how these two forces can harmoniously coexist to shape the future of visual art.