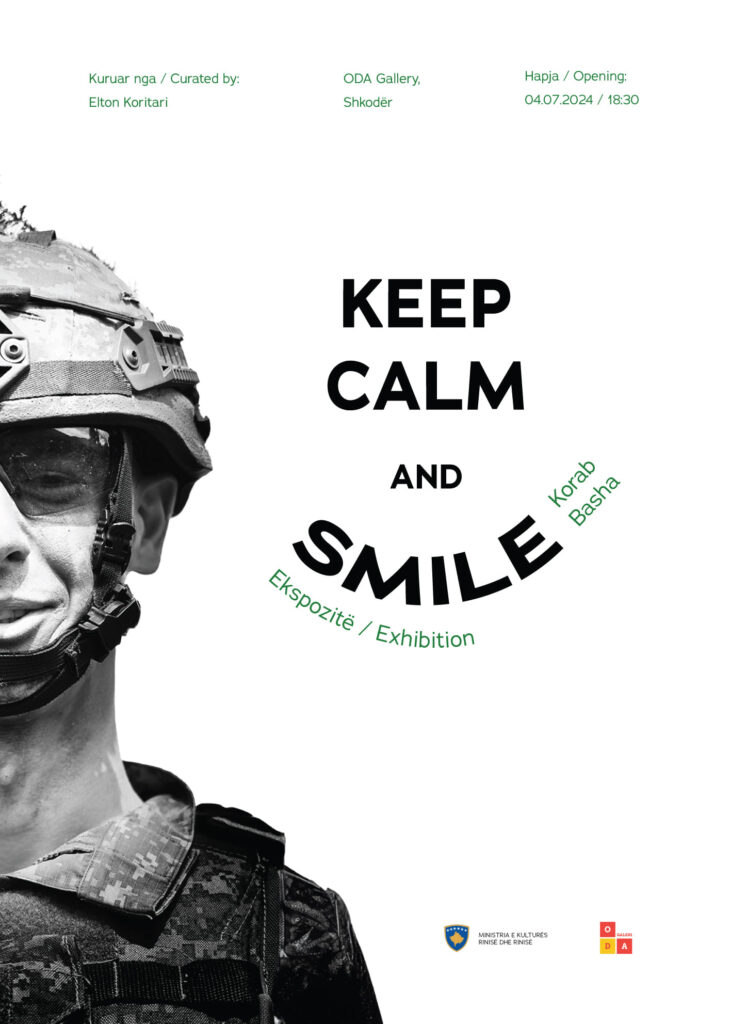

Exhibition: "KEEP CALM AND SMILE" by Korab Basha / Curated by Elton Koritari / 30.08.2024 / 19:00 / Grand Squere /

Photo: © Korab Basha

Ceremonil opening in front of Grand Hotel

EXHIBITION: “KEEP CALM AND SMILE” by Korab Basha / Curated by Elton Koritari

“QËNDRO I QETË DHE BUZËQESH” nga Korab Basha / Kurator: Elton Koritari

Titulli i këtij projekti ambicioz të fotografit Korab Basha, fjalë për fjalë mund të përkthehet “Qëndroni të qetë dhe buzëqeshni”. Basha ripërdor dhe riinterpreton sloganin e ushtrisë së Mbretërisë së Bashkuar i cili gjatë luftës së dytë botërore motivonte britanikët për të qëndruar të qetë dhe për të vazhduar, për të ecur, për të mbajtur gjallë optimizmin, pavarësisht kërcënimit të afërt të pushtimit nazist. Madje, edhe pse nuk u publikua kurrë në atë kohë por u rishfaq pas më shumë se 50 vitesh, ky slogan, me një rikthim triumfal në pop-kulturën bashkëkohore, vazhdon të jetë një simbol i fortë i rezistencës dhe durimit në përballje me sfidat e jetës, jo vetëm në aspektin propagandistik të tij. Në stuhinë e vazhdueshme të tensioneve ushtarake dhe politike, sot ushtria e Kosovës mishëron dhuntinë e të qendruarit në ballë të vendit dhe e bën këtë duke u mbështetur fort në humanizmin e saj.

FSK është një ushtri e qytetarëve të saj dhe kjo gjë paraqet një moment historik dhe të rëndësishëm në afirmimin ndërkombëtar të shtetit të Kosovës. “Keep Calm and Smile” thekson qëndrueshmërinë, integritetin moral dhe mbështetjen e fuqishme në popull të forcave të armatosura dhe simbolizon kështu një qasje të guximshme ndaj sfidave të Kosovës bashkëkohore. E akoma më shumë, në këtë ekspozitë, ata me buzëqeshjen e tyre përfaqësojnë forcën dhe krenarinë e popullit shqiptar në përballje me çdo sfidë, ashtu si përherë në historinë tonë. Vajzat dhe djemtë që mbushin sot rreshtat e kësaj ushtrie, janë pasqyrë e të gjithë kosovarëve që duan të lënë pas të kaluarën dhe në fund të shikojnë nga e ardhmja. Me një buzëqeshje.

FSK është e qartë si dielli se nuk ekziston për të sulmuar askënd, përkundrazi ajo vetëm mbron integritetin dhe pavarësinë e Republikës së Kosovës, ngritur mbi bazat e rezistenzës dhe qëndresës së Ushtrisë Çlirimtare, e cila lindi pikërisht për të mbrojtur njerëzit e saj të të masakruar prej dekadash, të lodhur nga një e kaluar mizore dhe të dërrmuar nga mohimi i parimit të vetëvendosjes. Sot, qytetarët e Kosovës, në shtetin e tyre të fituar me vetëmohim dhe sakrificë, ndjejnë më shumë se kurrë dëshirën për ta mbyllur me të shkuarën dhe më në fund të shikojnë të ardhmen drejt në sy, larg dhunës, të lirë. Me një projekt të qartë në vizionin e tij dhe me këmbëngulje të admirueshme për ta realizuar atë deri në fund, Korab Basha na tregon jo vetëm sesi ushtarët e Kosovës shohin pra nga e ardhmja, pikërisht ashtu siç ndihet dëshira për të ardhmen në zemrën e çdo qytetari kosovar por edhe se pas shumë vitesh ndërhyrjesh të çmuara nga ushtritë e huaja, është një arritje e madhe për Kosovën që të ketë një ushtri të sajën dhe më shumë se kurrë ta shijojë këtë simbolikë të vogël, por të madhe. Artisti hyn thellë edhe në kontekste më globale sesa trevat tona. Ai na sugjeron se në fund të fundit, paqja fillon me një buzëqeshje.

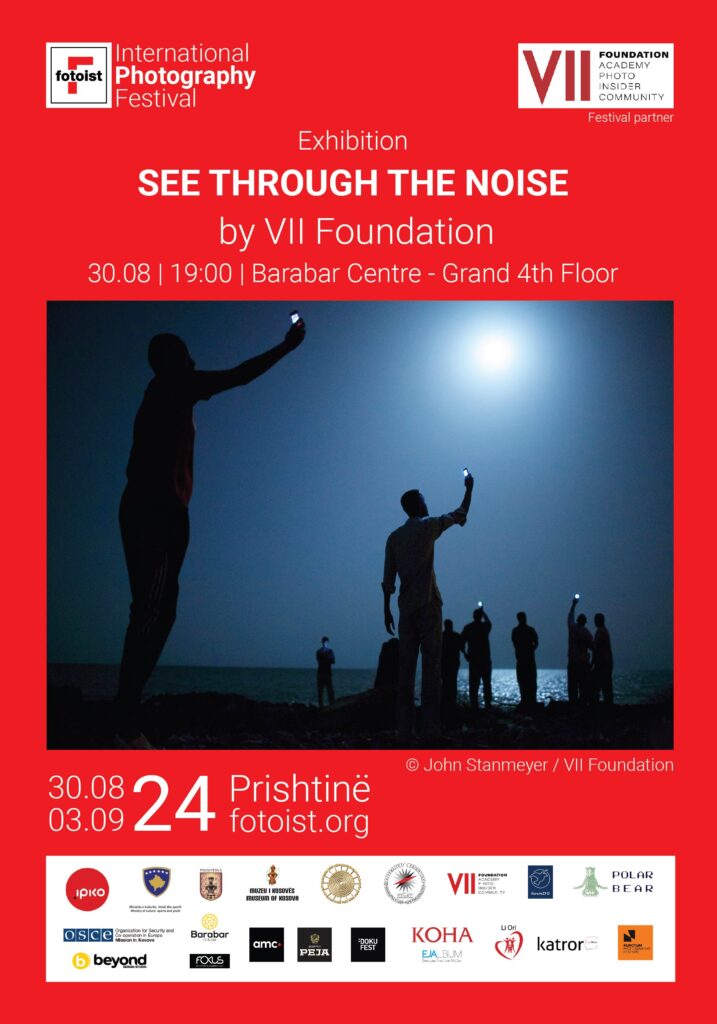

Photo: © John Stanmeyer / VII Foundation – African migrants on the shore of Djibouti City at night raise their phones in an attempt to catch an inexpensive signal from neighboring Somalia—a tenuous link to relatives abroad.

"SEE THROUGH THE NOISE" by VII Foundation

Exhibition: SEE THROUGH THE NOISE

Production & Curation: Ziyah Gafic / Gary Knight / Yonola Viguerie

The dawn of the digital era enabled the creation of VII on the 8th of September 2001. Three days later, Al Qaeda attacked the United States. In the following months, while the burning dust of the Twin Towers still choked New York, all seven founding members documented the violence that followed. In the ensuing years, as the narrative of the new century was being written, they photographed the invasion and occupation of Iraq, the wars in the Middle East, and the chaos that smothered an unjust world. The name VII became synonymous with courageous and impactful photojournalism.

VII went small and photographer-owned. The photographers believed in the power and energy of intimate collective effort at a time when corporations were acquiring smaller photo agencies and consolidating what had been a rich and diverse ecosystem into giant conglomerates. VII was created to give its members independence and enhance their ability to work on stories that mattered in partnership with the world’s leading press. It created new opportunities the photographers could not imagine. But the digital revolution that enabled the growth of VII also precipitated a catastrophic loss in revenue for its clients in the press.

Photojournalism means taking risks; it requires initiative, resourcefulness, empathy, and courage. It also involves trust, imagination, collaboration, and partnership. Publications and the photo agencies that served them were once essential partners in the life of a photojournalist. But trying to sell the news to a public that expects it for free means the press has fewer resources to deploy independent photographers and commission original work. Consequently, the media and photo agencies now have less impact and influence on the production of visual journalism. So, what next?

Anticipating the shrinking space the media would occupy in the lives of photographers, The VII Foundation was created to innovate and lead in the non-profit arena, unlimited by the constraints of the editorial marketplace. One of its objectives is to train and support photographers as they continue scrutinizing a world in turmoil and hold those who crave power to account. Ours is a world where leaders regard facts as optional, human rights as an inconvenience, and where it is increasingly difficult to differentiate between artifice and truth. Even the word truth is hard to explain — and is best defined by being the opposite of something — falsehood.

This was the first collective exhibition by VII in Arles, marking the acquisition of VII Photo by The VII Foundation in 2023. The featured photographs are among the most significant images depicting the events and issues they portray. They serve as an enduring testament to the importance, within our fragile societies, of a bold form of journalism that is free of artifice and falsehood — a pillar that is essential to The VII Foundation.

Encompassing photography bearing witness to historical events and critical review, selected work includes photography by:

Some of these works received the most coveted prizes in photography, such as World Press Photo of the Year, and were featured on pages of leading publications such as TIME magazine, National Geographic, Le Monde, The New York Times, Pari Match, others led to investigations to war crimes in Iraq and were used as court evidence in International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

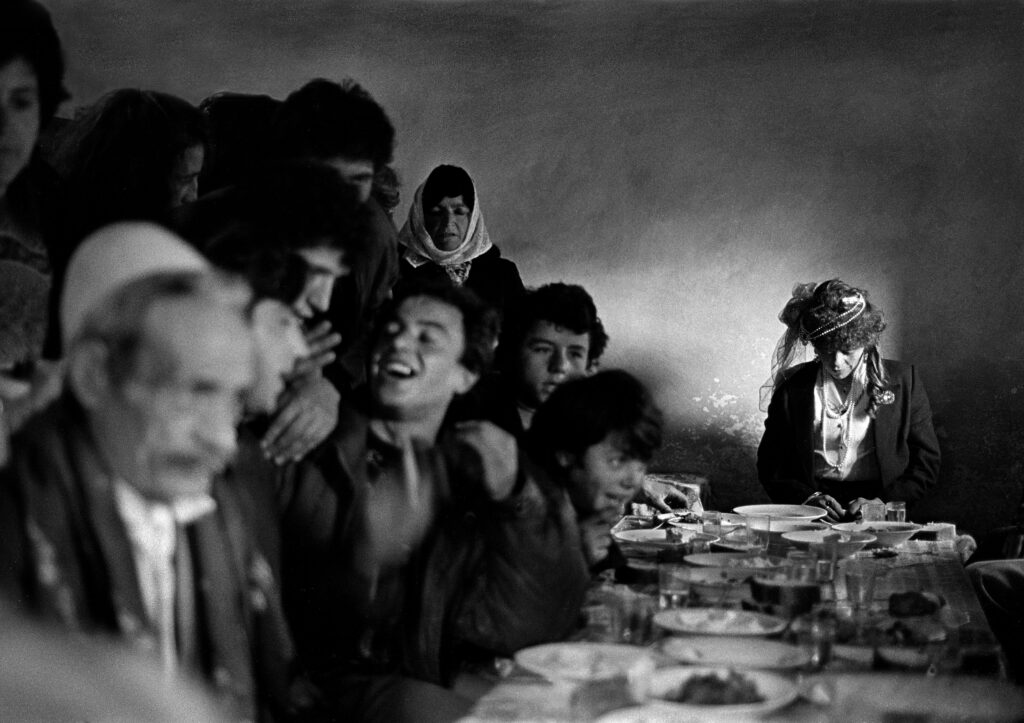

Exhibition: BEHIND THE VAIL by Barry Lewis

Albanian family in their Sunday best waiting for a ferry, Albania, 1991. Albanian family in their Sunday best waiting for the Koman Ferry to Bajram Curri in the North of Albania, 1991. © Barry Lewis

“Oh, we’re back in the Balkans again, back to the joy and the pain. What if it burns or it blows or it snows? We’re back to the Balkans again. Back, where tomorrow the quick may be dead, With a hole in his heart or a ball in his head. Back, where the passions are rapid and red, Oh, we’re back to the Balkans again!” Song of the Balkan Peninsula, Edith Durham, 1908 In the 1970’s, along with half of my generation, I believed that socialism was the way forward and made photographic journeys to the USSR, Cuba, East Germany and Romania. Strangely the country that exerted the strangest charm for me, without my having visited it, was Albania. Tales of a closed country, following an isolated Stalinist path of socialism, then turning its back on the Eastern bloc and embracing Maoism, was always fuelling my imagination. The hum and whistle of Radio Tirana with its flat monotonal commentary and its mix of martial and folk music triggered visions of a secret land behind mist-covered mountains. The excesses of the capitalist world vision epitomized by “Voice of America” had lost any allure for me, and a secretive country which banned beards, pornography, Americans, and idolised Norman Wisdom cried out to be visited. In 1990 I joined a group of twelve people, made up of spies, tourists, journalists, a retired farmer, a botanist and a rock musician, on an “archaeological study tour”. Between us we had about four words of Albanian, a 1960’s phrase book and a lot of fear, especially as the timing of the visit followed hard on the heels of the fall of the Berlin wall and fighting had just started in Kosova. We were taken from co-op to commune, listened to traditional folk singers and as a grand finale visited the Enver Hoxha state tractor factory (devoid of tractors). Between the lines, however, we could see a country in its death throes. People whispered at night of demonstrations and unrest, asking endless questions about the West and… Norman Wisdom. We were one of a few groups to visit Shkodra and made a limited trip to the north where, in the inaccessible mountains, a way of life had resisted forty years of repression. Here in these isolated heights, village and tribal life was based on the Kanun, a rigid set of codes from medieval times, based on honour and blood. My interest was whetted, fed by fantasy and reading Edith Durham’s accounts of living with the “Mountaineers” in her book, ‘High Albania’. President Hoxha died in 1985 and in a wave of riots signalling the end of the one-party state, his statue was toppled on 21st February, 1991. I returned to the country with the writer Ian Thompson in March as the mountain snows melted and access to the northern mountains became possible. The area had been closed to foreigners for forty years as Hoxha’s party control had encountered real problems with the fiercely independent population of the region. The journey, this time, was better organised. It needed to be. The country was in a state of anarchy and navigating our way on the difficult roads, anger and crime were a constant reminder of life as it had been. We were lucky to be some of the first Westerners to meet the generous people of the highlands who took us into their homes and fed us despite severe shortages. People followed their law “Our house belongs to God and guest” and we were always under the host’s protection and given both food and gracious company. When we came upon the mournful funeral of a young man in the village of Kalimash, way up in the mountains, not only did they let a stranger photograph a painful and deeply personal ritual, but we were taken to the father’s house where gifts of food were thrust on us, with the words: “We are so sorry. It is our custom to place a roasted sheep on the table in front of guests. But we don’t have the means anymore.” Europe was changing at an unprecedented pace, through technology and the free flow of people, this corner of the Balkans was moving from a closed society, full of dark secrets and fierce bravery on it’s difficult and journey towards a new beginning. I hope this work honours these people! BARRY LEWIS Barry Lewis started as a chemistry teacher with photography as a hobby. Barry stopped teaching in 1974 when he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art where he studied under Bill Brandt. In 1976 he won the Vogue award and worked for a year with the magazine. In 1977 he received an arts council grant to photograph commuting in London, which was exhibited in the Museum of London and the Southbank. In 1981 & 83 he was exhibited in the Photographers Gallery, for ‘New Work on Britain’ and a solo show, ‘A Week in Moscow’ Working mainly for magazines, in 1999 he was a co-founder of the photo agency Network which played an important role in British Photojournalism for over 20 years. A regular contributor to Life Magazine, National Geographic, and the Sunday Times, Barry has worked globally until 2014 and made over 20 books. He has exhibited throughout the world and received several awards including the Leica medal for humanitarian photography. From 2015 for 5 years Barry worked mainly on documentary films but has returned to photography in 2021 when he started his current work, “Intersections”: a study of London through portraits and words of the people.

Exhibition: "HOUSE FOR SALE" by Imre Szabó / 30.08.2024 / 19:00 / Barabar Centre - Grand 4th Floor /

Photo Copyright: Imre Szabó – Funeral of ethnic Albanian victims of a battle between the Kosovo Liberation Army and Serbian forces, Likoshan, March 1998.

EXHIBITION: “HOUSE FOR SALE” by Imre Szabó

“Kid, it’s a mess down there, but don’t just capture all the bad and broken stuff. Capture something we can use to illustrate texts. ”These were the words that Mirko Bojić, the then editor-in-chief of “Illustrated Politics,” used to see off Imre Szabo ahead of his first photographic assignment in Kosovo in 1981. He was probably unaware that, by sending him, he was doing an extremely significant thing for the creation of one of the most important photo archives of Kosovo from 1981 to 1999. “When we published the photograph and the story House for Sale about how Serbs were selling their property and leaving Kosovo, I did not expect such reactions at all. We stumbled upon a grandmother completely by chance, sitting under a tree and peeling potatoes, and there was a sign “House for Sale” on the tree. After that, the same night, we visited Branko Đurica, then the deputy editor-in-chief, to tell him about that conversation. He immediately called the editor-in-chief and said we are changing the cover. This is how the photograph and the story ended up on the cover. It was all this strange to me. When the story came out, we were attacked from Serbia, being asked what we were doing and why we were stirring up the people. “When Milošević went down there, I was convinced that he was really going to calm things down, that he had sincere intentions. However, when I attended those meetings and rallies, it became clear to me that nothing of that sort was happening.”

“Ever since I learned to speak Serbian, I haven’t had any problems based on nationality in Yugoslavia. This is why some things that awaited me in Kosovo were completely unimaginable from my perspective.”

Born in Mokrin, Serbia, in 1956, Imre completed high school in Kikinda and studied German Language and Literature at the Faculty of Philology, Belgrade University. He has been publishing photos since 1974 and has participated in over 200 exhibitions both domestically and internationally, earning numerous awards. His solo exhibitions have been held in Kikinda, Mokrin, Skopje, Belgrade, Banatski Brestovac, Ankara, Maribor, Paraćin, Kragujevac, Niš, and Istanbul.

He contributed to the “Light and Shadows on the Balkans” exhibition with 10 photos, displayed in Belgrade (2009), Bucharest (2010), Istanbul (2010), and Ankara (2010). He also participated in the “Lessons from ’91” project (2016 and 2017), which was exhibited in Zagreb, Belgrade, Berlin, and Maribor.

A professional photographer since 1980, Szabó began his career as a newspaper photographer at “Ilustrovana Politika” until 1989. He briefly worked at the daily newspaper “Politika” before moving to “Intervju” until autumn 1991 and then to “Nin” until 1995, after which he pursued applied photography independently. He has also served as a photography editor at the daily newspaper Danas, the weekly magazine Blic News, Novi magazin, Status monthly magazine, and for the news agency Fonet.

His work has been published in numerous significant international journals such as Stern, Focus, Spiegel, Mond, Lexpress, Time, Newsweek, Herald Tribune, and Le Nouvell Observateur, as well as in most Yugoslav newspapers and many monographs, catalogues, and publications.

He has been a member of ULUPUDS (Association of Serbian Applied Artists) since 1985 and is currently a freelance photographer based in Belgrade, Serbia.

Photo Copyright: Imre Szabo – Slobodan Milosevic makes a speech at Fushë Kosovë, 1987.